The Snow

The Snow Polystom (Gollancz Sf S.)

Polystom (Gollancz Sf S.) The Parodies Collection

The Parodies Collection The Man Who Would Be Kling

The Man Who Would Be Kling Bête

Bête The Lake Boy

The Lake Boy Polystom

Polystom Swiftly: A Novel (GollanczF.)

Swiftly: A Novel (GollanczF.) Jack Glass

Jack Glass Haven

Haven The Riddles of The Hobbit

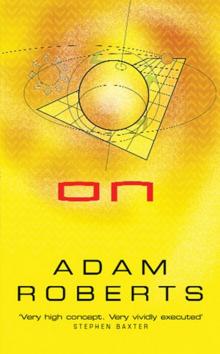

The Riddles of The Hobbit On

On The Wonga Coup

The Wonga Coup The Thing Itself

The Thing Itself Anticopernicus

Anticopernicus New Model Army

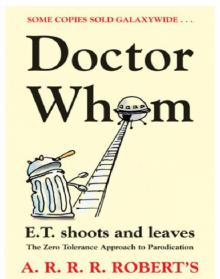

New Model Army Doctor Whom or ET Shoots and Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Parodication

Doctor Whom or ET Shoots and Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Parodication On (GollanczF.)

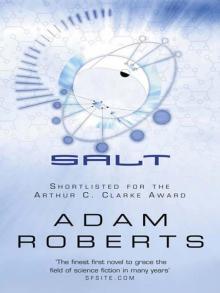

On (GollanczF.) Salt

Salt Salt (GollanczF.)

Salt (GollanczF.) By Light Alone

By Light Alone Yellow Blue Tibia

Yellow Blue Tibia Gradisil (GollanczF.)

Gradisil (GollanczF.) Land Of The Headless (GollanczF.)

Land Of The Headless (GollanczF.) Adam Robots: Short Stories

Adam Robots: Short Stories Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea

Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea